Last week I gave a talk at the Philly Tech Week 2015 Dev Day organized by the delightful people at technical.ly on some of the tricks/strategies we use in the Firefox OS Gaia Email app. Note that the credit for implementing most of these techniques goes to the owner of the Email app’s front-end, James Burke. Also, a special shout-out to Vivien for the initial DOM Worker patches for the email app.

I tried to avoid having slides that both I would be reading aloud as the audience read silently, so instead of slides to share, I have the talk script. Well, I also have the slides here, but there’s not much to them. The headings below are the content of the slides, except for the one time I inline some code. Note that the live presentation must have differed slightly, because I’m sure I’m much more witty and clever in person than this script would make it seem…

Cover Slide: Who!

Hi, my name is Andrew Sutherland. I work at Mozilla on the Firefox OS Email Application. I’m here to share some strategies we used to make our HTML5 app Seem faster and sometimes actually Be faster.

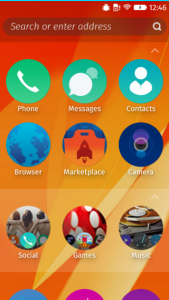

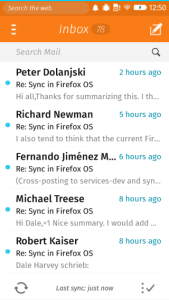

What’s A Firefox OS (Screenshot Slide)

But first: What is a Firefox OS? It’s a multiprocess Firefox gecko engine on an android linux kernel where all the apps including the system UI are implemented using HTML5, CSS, and JavaScript. All the apps use some combination of standard web APIs and APIs that we hope to standardize in some form.

Here are some screenshots. We’ve got the default home screen app, the clock app, and of course, the email app.

It’s an entirely client-side offline email application, supporting IMAP4, POP3, and ActiveSync. The goal, like all Firefox OS apps shipped with the phone, is to give native apps on other platforms a run for their money.

And that begins with starting up fast.

Fast Startup: The Problems

But that’s frequently easier said than done. Slow-loading websites are still very much a thing.

The good news for the email application is that a slow network isn’t one of its problems. It’s pre-loaded on the phone. And even if it wasn’t, because of the security implications of the TCP Web API and the difficulty of explaining this risk to users in a way they won’t just click through, any TCP-using app needs to be a cryptographically signed zip file approved by a marketplace. So we do load directly from flash.

However, it’s not like flash on cellphones is equivalent to an infinitely fast, zero-latency network connection. And even if it was, in a naive app you’d still try and load all of your HTML, CSS, and JavaScript at the same time because the HTML file would reference them all. And that adds up.

It adds up in the form of event loop activity and competition with other threads and processes. With the exception of Promises which get their own micro-task queue fast-lane, the web execution model is the same as all other UI event loops; events get scheduled and then executed in the same order they are scheduled. Loading data from an asynchronous API like IndexedDB means that your read result gets in line behind everything else that’s scheduled. And in the case of the bulk of shipped Firefox OS devices, we only have a single processor core so the thread and process contention do come into play.

So we try not to be a naive.

Seeming Fast at Startup: The HTML Cache

If we’re going to optimize startup, it’s good to start with what the user sees. Once an account exists for the email app, at startup we display the default account’s inbox folder.

What is the least amount of work that we can do to show that? Cache a screenshot of the Inbox. The problem with that, of course, is that a static screenshot is indistinguishable from an unresponsive application.

So we did the next best thing, (which is) we cache the actual HTML we display. At startup we load a minimal HTML file, our concatenated CSS, and just enough Javascript to figure out if we should use the HTML cache and then actually use it if appropriate. It’s not always appropriate, like if our application is being triggered to display a compose UI or from a new mail notification that wants to show a specific message or a different folder. But this is a decision we can make synchronously so it doesn’t slow us down.

Local Storage: Okay in small doses

We implement this by storing the HTML in localStorage.

Important Disclaimer! LocalStorage is a bad API. It’s a bad API because it’s synchronous. You can read any value stored in it at any time, without waiting for a callback. Which means if the data is not in memory the browser needs to block its event loop or spin a nested event loop until the data has been read from disk. Browsers avoid this now by trying to preload the Entire contents of local storage for your origin into memory as soon as they know your page is being loaded. And then they keep that information, ALL of it, in memory until your page is gone.

So if you store a megabyte of data in local storage, that’s a megabyte of data that needs to be loaded in its entirety before you can use any of it, and that hangs around in scarce phone memory.

To really make the point: do not use local storage, at least not directly. Use a library like localForage that will use IndexedDB when available, and then fails over to WebSQLDatabase and local storage in that order.

Now, having sufficiently warned you of the terrible evils of local storage, I can say with a sorta-clear conscience… there are upsides in this very specific case.

The synchronous nature of the API means that once we get our turn in the event loop we can act immediately. There’s no waiting around for an IndexedDB read result to gets its turn on the event loop.

This matters because although the concept of loading is simple from a User Experience perspective, there’s no standard to back it up right now. Firefox OS’s UX desires are very straightforward. When you tap on an app, we zoom it in. Until the app is loaded we display the app’s icon in the center of the screen. Unfortunately the standards are still assuming that the content is right there in the HTML. This works well for document-based web pages or server-powered web apps where the contents of the page are baked in. They work less well for client-only web apps where the content lives in a database and has to be dynamically retrieved.

The two events that exist are:

“DOMContentLoaded” fires when the document has been fully parsed and all scripts not tagged as “async” have run. If there were stylesheets referenced prior to the script tags, the script tags will wait for the stylesheet loads.

“load” fires when the document has been fully loaded; stylesheets, images, everything.

But none of these have anything to do with the content in the page saying it’s actually done. This matters because these standards also say nothing about IndexedDB reads or the like. We tried to create a standards consensus around this, but it’s not there yet. So Firefox OS just uses the “load” event to decide an app or page has finished loading and it can stop showing your app icon. This largely avoids the dreaded “flash of unstyled content” problem, but it also means that your webpage or app needs to deal with this period of time by displaying a loading UI or just accepting a potentially awkward transient UI state.

(Trivial HTML slide)

<link rel=”stylesheet” ...> <script ...></script> DOMContentLoaded!

This is the important summary of our index.html.

We reference our stylesheet first. It includes all of our styles. We never dynamically load stylesheets because that compels a style recalculation for all nodes and potentially a reflow. We would have to have an awful lot of style declarations before considering that.

Then we have our single script file. Because the stylesheet precedes the script, our script will not execute until the stylesheet has been loaded. Then our script runs and we synchronously insert our HTML from local storage. Then DOMContentLoaded can fire. At this point the layout engine has enough information to perform a style recalculation and determine what CSS-referenced image resources need to be loaded for buttons and icons, then those load, and then we’re good to be displayed as the “load” event can fire.

After that, we’re displaying an interactive-ish HTML document. You can scroll, you can press on buttons and the :active state will apply. So things seem real.

Being Fast: Lazy Loading and Optimized Layers

But now we need to try and get some logic in place as quickly as possible that will actually cash the checks that real-looking HTML UI is writing. And the key to that is only loading what you need when you need it, and trying to get it to load as quickly as possible.

There are many module loading and build optimizing tools out there, and most frameworks have a preferred or required way of handling this. We used the RequireJS family of Asynchronous Module Definition loaders, specifically the alameda loader and the r-dot-js optimizer.

One of the niceties of the loader plugin model is that we are able to express resource dependencies as well as code dependencies.

RequireJS Loader Plugins

var fooModule = require('./foo');var htmlString = require('text!./foo.html');var localizedDomNode = require('tmpl!./foo.html');

The standard Common JS loader semantics used by node.js and io.js are the first one you see here. Load the module, return its exports.

But RequireJS loader plugins also allow us to do things like the second line where the exclamation point indicates that the load should occur using a loader plugin, which is itself a module that conforms to the loader plugin contract. In this case it’s saying load the file foo.html as raw text and return it as a string.

But, wait, there’s more! loader plugins can do more than that. The third example uses a loader that loads the HTML file using the ‘text’ plugin under the hood, creates an HTML document fragment, and pre-localizes it using our localization library. And this works un-optimized in a browser, no compilation step needed, but it can also be optimized.

So when our optimizer runs, it bundles up the core modules we use, plus, the modules for our “message list” card that displays the inbox. And the message list card loads its HTML snippets using the template loader plugin. The r-dot-js optimizer then locates these dependencies and the loader plugins also have optimizer logic that results in the HTML strings being inlined in the resulting optimized file. So there’s just one single javascript file to load with no extra HTML file dependencies or other loads.

We then also run the optimizer against our other important cards like the “compose” card and the “message reader” card. We don’t do this for all cards because it can be hard to carve up the module dependency graph for optimization without starting to run into cases of overlap where many optimized files redundantly include files loaded by other optimized files.

Plus, we have another trick up our sleeve:

Seeming Fast: Preloading

Preloading. Our cards optionally know the other cards they can load. So once we display a card, we can kick off a preload of the cards that might potentially be displayed. For example, the message list card can trigger the compose card and the message reader card, so we can trigger a preload of both of those.

But we don’t go overboard with preloading in the frontend because we still haven’t actually loaded the back-end that actually does all the emaily email stuff. The back-end is also chopped up into optimized layers along account type lines and online/offline needs, but the main optimized JS file still weighs in at something like 17 thousand lines of code with newlines retained.

So once our UI logic is loaded, it’s time to kick-off loading the back-end. And in order to avoid impacting the responsiveness of the UI both while it loads and when we’re doing steady-state processing, we run it in a DOM Worker.

Being Responsive: Workers and SharedWorkers

DOM Workers are background JS threads that lack access to the page’s DOM, communicating with their owning page via message passing with postMessage. Normal workers are owned by a single page. SharedWorkers can be accessed via multiple pages from the same document origin.

By doing this, we stay out of the way of the main thread. This is getting less important as browser engines support Asynchronous Panning & Zooming or “APZ” with hardware-accelerated composition, tile-based rendering, and all that good stuff. (Some might even call it magic.)

When Firefox OS started, we didn’t have APZ, so any main-thread logic had the serious potential to result in janky scrolling and the impossibility of rendering at 60 frames per second. It’s a lot easier to get 60 frames-per-second now, but even asynchronous pan and zoom potentially has to wait on dispatching an event to the main thread to figure out if the user’s tap is going to be consumed by app logic and preventDefault called on it. APZ does this because it needs to know whether it should start scrolling or not.

And speaking of 60 frames-per-second…

Being Fast: Virtual List Widgets

…the heart of a mail application is the message list. The expected UX is to be able to fling your way through the entire list of what the email app knows about and see the messages there, just like you would on a native app.

This is admittedly one of the areas where native apps have it easier. There are usually list widgets that explicitly have a contract that says they request data on an as-needed basis. They potentially even include data bindings so you can just point them at a data-store.

But HTML doesn’t yet have a concept of instantiate-on-demand for the DOM, although it’s being discussed by Firefox layout engine developers. For app purposes, the DOM is a scene graph. An extremely capable scene graph that can handle huge documents, but there are footguns and it’s arguably better to err on the side of fewer DOM nodes.

So what the email app does is we create a scroll-region div and explicitly size it based on the number of messages in the mail folder we’re displaying. We create and render enough message summary nodes to cover the current screen, 3 screens worth of messages in the direction we’re scrolling, and then we also retain up to 3 screens worth in the direction we scrolled from. We also pre-fetch 2 more screens worth of messages from the database. These constants were arrived at experimentally on prototype devices.

We listen to “scroll” events and issue database requests and move DOM nodes around and update them as the user scrolls. For any potentially jarring or expensive transitions such as coordinate space changes from new messages being added above the current scroll position, we wait for scrolling to stop.

Nodes are absolutely positioned within the scroll area using their ‘top’ style but translation transforms also work. We remove nodes from the DOM, then update their position and their state before re-appending them. We do this because the browser APZ logic tries to be clever and figure out how to create an efficient series of layers so that it can pre-paint as much of the DOM as possible in graphic buffers, AKA layers, that can be efficiently composited by the GPU. Its goal is that when the user is scrolling, or something is being animated, that it can just move the layers around the screen or adjust their opacity or other transforms without having to ask the layout engine to re-render portions of the DOM.

When our message elements are added to the DOM with an already-initialized absolute position, the APZ logic lumps them together as something it can paint in a single layer along with the other elements in the scrolling region. But if we start moving them around while they’re still in the DOM, the layerization logic decides that they might want to independently move around more in the future and so each message item ends up in its own layer. This slows things down. But by removing them and re-adding them it sees them as new with static positions and decides that it can lump them all together in a single layer. Really, we could just create new DOM nodes, but we produce slightly less garbage this way and in the event there’s a bug, it’s nicer to mess up with 30 DOM nodes displayed incorrectly rather than 3 million.

But as neat as the layerization stuff is to know about on its own, I really mention it to underscore 2 suggestions:

1, Use a library when possible. Getting on and staying on APZ fast-paths is not trivial, especially across browser engines. So it’s a very good idea to use a library rather than rolling your own.

2, Use developer tools. APZ is tricky to reason about and even the developers who write the Async pan & zoom logic can be surprised by what happens in complex real-world situations. And there ARE developer tools available that help you avoid needing to reason about this. Firefox OS has easy on-device developer tools that can help diagnose what’s going on or at least help tell you whether you’re making things faster or slower:

– it’s got a frames-per-second overlay; you do need to scroll like mad to get the system to want to render 60 frames-per-second, but it makes it clear what the net result is

– it has paint flashing that overlays random colors every time it paints the DOM into a layer. If the screen is flashing like a discotheque or has a lot of smeared rainbows, you know something’s wrong because the APZ logic is not able to to just reuse its layers.

– devtools can enable drawing cool colored borders around the layers APZ has created so you can see if layerization is doing something crazy

There’s also fancier and more complicated tools in Firefox and other browsers like Google Chrome to let you see what got painted, what the layer tree looks like, et cetera.

And that’s my spiel.

Links

The source code to Gaia can be found at https://github.com/mozilla-b2g/gaia

The email app in particular can be found at https://github.com/mozilla-b2g/gaia/tree/master/apps/email

(I also asked for questions here.)